Attacks against Machine Learning Privacy (Part 2): Membership Inference Attacks with TensorFlow Privacy

Published:

Welcome to the second part of my series about attacks against machine learning (ML) privacy. If you haven’t checked out my last post about model inversion attacks yet, feel free to do so. It might also serve you as a short introduction about the topic of ML privacy in general. For today’s post I am going to assume that you have some understanding of the most common concepts in ML.

All right, let’s get started. The privacy risk I am going to present today is called “membership inference”. We’ll first have a look on what membership inference actually means and how it can be used in order to violate individual privacy. Afterwards, we’ll go into some more details exploring how those attacks work. Then, we’ll use the TensorFlow Privacy library in order to conduct an attack on an ML classifier ourselves. You will see that this powerful tool makes it pretty easy. I will also briefly mention some factors that increase a model’s vulnerability against membership inference attacks and protective measures.

This blogpost has been updated in December 2021 for TensorFlow Privacy version 0.7.3.

Part 1: Membership Inference Attacks

Membership inference attacks were first described by Shokri et al. [1] in 2017. Since then, a lot of research has been conducted in order to make these attacks more efficient, to measure the membership risk of a given model, and to mitigate the risks.

Let’s first have a superficial look on the topic before diving deep into the algorithmic background and attack structure.

Overview on Membership Inference Attacks

The aim of a membership inference attack is quite straight forward: Given a trained ML model and some data point, decide whether this point was part of the model’s training sample or not. You might not see the privacy risk right away, but think of the following situation:

Imagine you are in a clinical context. There, you may have an ML model that is supposed to predict an adequate medical treatment for cancer patients. This model, naturally, needs to be trained on the data of cancer patients. Hence, given a data point, if you are able to determine that it was indeed part of the model’s training data, you will know that the corresponding patient must have cancer. As a consequence, this patient’s privacy would be disclosed.

I hope that with this example I could convince you of the importance of membership privacy. Basically, in any context where the sheer fact of being included in a sample can be privacy disclosing, membership inference attacks pose a severe risk.

How do Membership Inference Attacks Work?

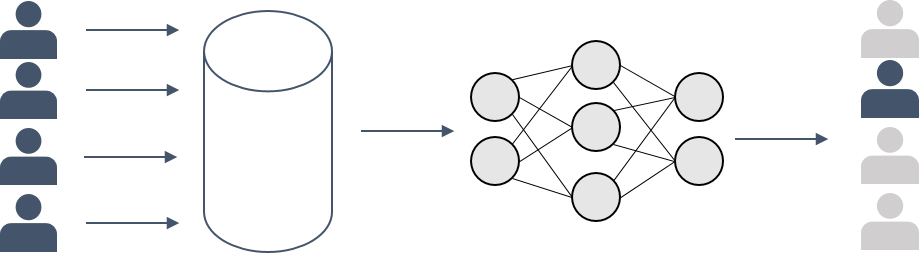

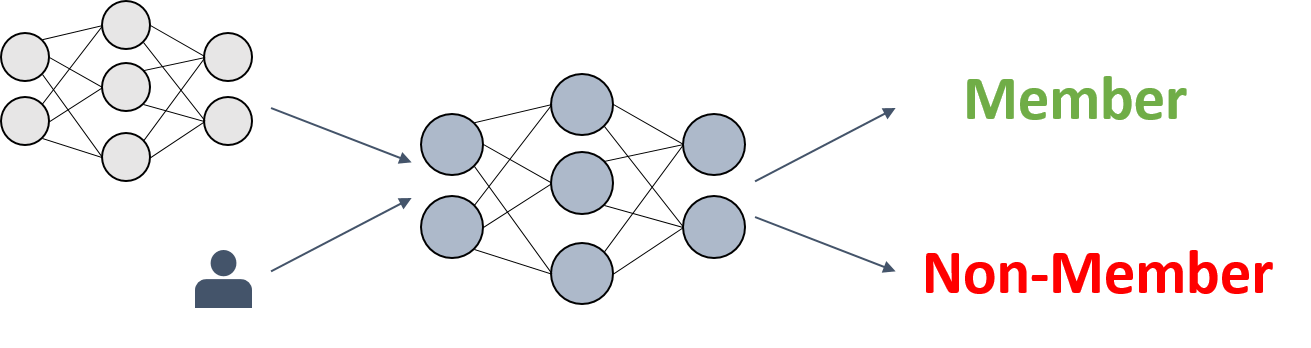

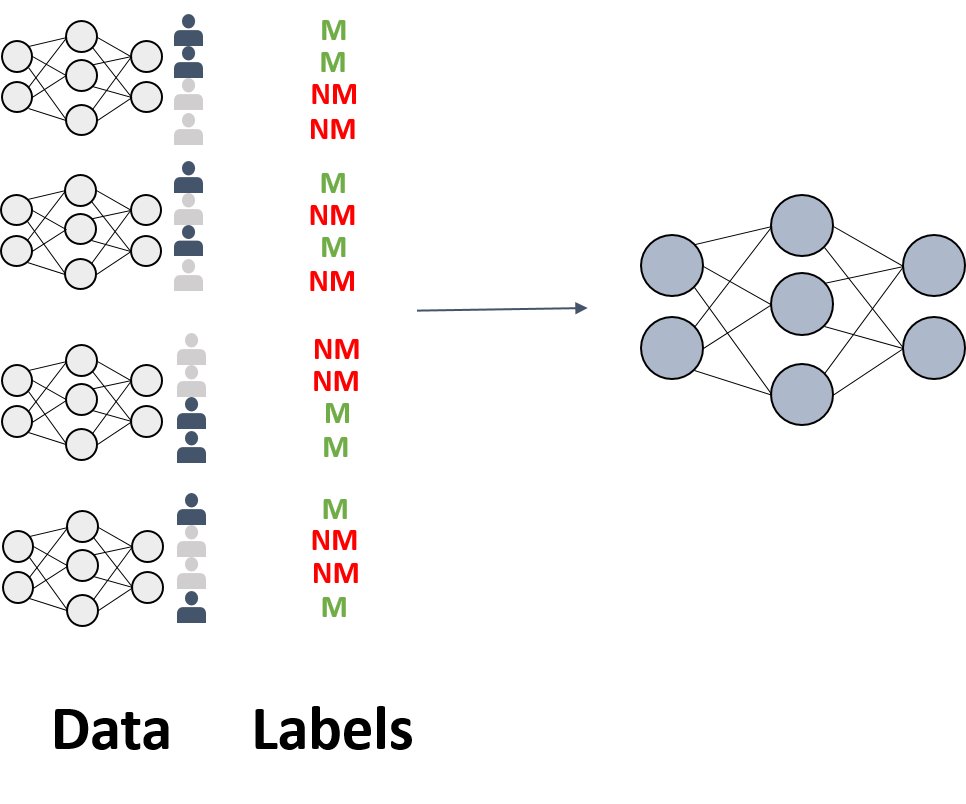

Most membership inference attacks work similar as the original example described by Shokri et al. [1], namely by building a binary meta-classifier $f_{attack}$ that, given a model $f$ and a data point $x_i$, decides whether or not $x_i$ was part of the model’s training sample $X$.

In order to train this meta-classifier $f_{attack}$, $k$ shadow models $f_{shaddow}^j$ are constructed. Those models are supposed to imitate the behaviour of the original ML model $f$. However, their training data $X’$, i.e. the ground truth $y’$ for the binary classifications, is known to the attacker.

By using the knowledge about the shadow models’ training data, input output-pairs ($x_i’, f_{shaddow}^j; y_i’$) for the meta-classifier can be constructed, such that it learns the task of distinguishing between members and non-members based on an ML model’s behavior on them.

Shokri et al. [1] claim that the more shadow models one uses, the more accurate the attack will be. The authors also describe several methods for creating $X’$, e.g. based on noisy real-world data that is similar to the original $X$, or based on data synthetization with help of $f$ or statistics over $X$. Additionally, they showed that a membership inference attack can even be trained with only black-box access to the target model and without any prior knowledge about its training data.

Implementing Membership Inference Attacks

There are several tools for implementing membership inference attacks. The two that I am most familiar with are the IBM-ART framework that I used in my last blogpost in order to implement model inversion attacks, and TensorFlow Privacy’s Membership Inference. For my purposes (mainly trying to compare privacy between different models), so far, the TensorFlow version has proven more useful, since the attacks were more successful. Therefore, in the following, we are going to take a look at the implementation of membership inference attacks with TensorFlow Privacy . Similar to last time, I’ve uploaded a notebook for you, containing my entire code. The code was updated in December 2021 for Python 3.7, TensorFlow 2.7, and TensorFlow Privacy 0.7.3.

TensorFlow Privacy’s Membership Inference-Framework

Internally, TensorFlow Privacy’s Membership Inference attack differs slightly from the original attack as described by Shokri et al. [1]. Instead of training several shadow models, it relies on the observation by Salem et al. [5] that using the original model’s predictions on the target points is sufficient to deduce their membership. Thereby, no training of any shadow model that approximates the original model’s behavior is required which makes the attack more sufficient. In this setting, the original model under attack kind of serves itself as a “shadow model” that approximates its own behavior perfectly.

In my opinion, the usability of TensorFlow Privacy’s Membership Inference attack has had its ups and downs in the last months. For a long time, TensorFlow Privacy used to work with TensorFlow version 1 only. For me, this included a lot of hassle by continuously changing between virtual environments with TensorFlow version 1 and 2 in order to take the maximum capabilities out of both versions. Then, by the end of 2020, TensorFlow Privacy was successfully updated to work with Tensorflow 2 and I was all excited about it. However, in my opinion, there are still some ongoing problems if you want to include the membership inference attacks into longer-lasting projects: For example, if I am not mistaken, the interface of TensorFlow Privacy’s membership inference has been updated and changed completely WITHOUT a version number increase so far (stayed 0.5.1 all along). So, don’t be confused if your package 0.5.1 has entirely different code than the one that you find in the online repo, or if you can’t get your old code to run. In order to always stay up to date, the helpful community suggested using the following

pip install -U git+https://github.com/tensorflow/privacy

and it works.

Update December 2021: Things seem to be getting more and more stable. After a major refactoring in a previous version, the interface in version 0.7.3 (the one that I am referring to in the updated version of this blogpost) has not changed and can be used as described here.

Implementing a Membership Inference Attack with TensorFlow Privacy

When evaluating membership inference risks, I prefer to work with the CIFAR10 dataset instead of MNIST because, according to my experience, the membership privacy risk of simple models trained with MNIST is usually already quite low. Therefore, one barely sees any changes when trying to mitigate membership privacy risks by implementing counter measures.

For those of you who are not familiar with the CIFAR10 dataset: it’s another dataset that you can directly load through keras:

train, test = tf.keras.datasets.cifar10.load_data()

It consists of 60000 32x32 colour images in 10 classes, with 6000 images per class (50000 training images and 10000 test images). The classes are airplane, automobile, bird, cat, deer, dog, frog, horse, ship, and truck.

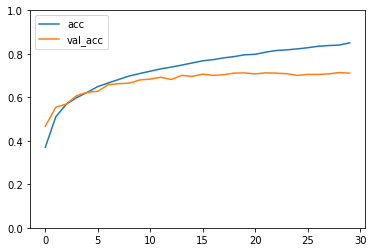

With its three color channels and details, this dataset is more complex than MNIST. In order to see some privacy risks, we will use a fairly simple architecture here without a lot of regularization (which might mitigate membership privacy risks, see below).

def make_simple_model():

""" Define a Keras model without much of regularization

Such a model is prone to overfitting"""

shape = (32, 32, 3)

i = Input(shape=shape)

x = Conv2D(32, (3, 3), activation='relu')(i)

x = MaxPooling2D()(x)

x = Conv2D(64, (3, 3), activation='relu')(x)

x = MaxPooling2D()(x)

x = Conv2D(64, (3, 3), activation='relu')(x)

x = MaxPooling2D()(x)

x = Flatten()(x)

x = Dense(128, activation='relu')(x)

x = Dense(10)(x)

model = Model(i, x)

return model

Based on this architecture, we can build our model.

model = make_simple_model()

# specify parameters

optimizer = tf.keras.optimizers.Adam()

loss = tf.keras.losses.SparseCategoricalCrossentropy(from_logits=True)

# compile the model

model.compile(optimizer=optimizer, loss=loss, metrics=['accuracy'])

history = model.fit(train_data, train_labels,

validation_data=(test_data, test_labels),

batch_size=128,

epochs=10)

In order to use TensorFlow Privacy’s membership inference attack, we need to import:

import tensorflow_privacy.privacy.privacy_tests.membership_inference_attack.membership_inference_attack as mia

from tensorflow_privacy.privacy.privacy_tests.membership_inference_attack.data_structures import AttackInputData

from tensorflow_privacy.privacy.privacy_tests.membership_inference_attack.data_structures import SlicingSpec

from tensorflow_privacy.privacy.privacy_tests.membership_inference_attack.data_structures import AttackType

The first line imports the membership inference attack itself. The following lines import data structures required in the course of the attack.

The library offers so many different functionalities that - for non-experts - it might be a little difficult to identify the right setting even though the README is very helpful.

However, to find some useful information (e.g., what data you must provide, and which one is optional, or what type this data should have), one needs to dive deep into the code. Therefore, I will give you a summary of my findings here.

AttackInputData is used to specify what information $f_{attack}$ will receive. As we have clarified above, $f_{attack}$ is the binary classifier trained to predict, based on a target model $f$’s output given a data point, whether this data point was part of the training data or not. And exactly this output of our model $f$ can be provided through the AttackInputData data structure. You can specify

train and test losstrain and test labels(as integer arrays)train and test entropytrain and test logitsortrain and test probabilitiesover all given classes. As the latter depend on the former, they can only be specified if no logits are provided.

Either labels, logits, losses or entropy should be set to be able to perform the attack. I have never worked with the entropy option so far, but the other values could potentially be obtained from your trained model with the following code.:

print('Predict on train...')

logits_train = model.predict(train_data)

print('Predict on test...')

logits_test = model.predict(test_data)

print('Apply softmax to get probabilities from logits...')

prob_train = tf.nn.softmax(logits_train, axis=-1)

prob_test = tf.nn.softmax(logits_test)

print('Compute losses...')

cce = tf.keras.backend.categorical_crossentropy

constant = tf.keras.backend.constant

y_train_onehot = to_categorical(train_labels)

y_test_onehot = to_categorical(test_labels)

loss_train = cce(constant(y_train_onehot), constant(prob_train), from_logits=False).numpy()

loss_test = cce(constant(y_test_onehot), constant(prob_test), from_logits=False).numpy()

SlicingSpec offers you a possibility to slice your dataset. This makes sense if you want to determine the success of the membership inference attack over specific data groups or classes. According to the code you have the following options that can be set to True:

- entire_dataset: one of the slices will be the entire dataset

- by_class: one slice per class is generated

- by_percentiles: generates 10 slices for percentiles of the loss - 0-10%, 10-20%, … 90-100%

- by_classification_correctness: creates one slice for correctly classified data points, and one for misclassified data points.

AttackType gives you different options on how your membership inference attack should be conducted.

- LOGISTIC_REGRESSION = ‘lr’

- MULTI_LAYERED_PERCEPTRON = ‘mlp’

- RANDOM_FOREST = ‘rf’

- K_NEAREST_NEIGHBORS = ‘knn’

- THRESHOLD_ATTACK = ‘threshold’

- THRESHOLD_ENTROPY_ATTACK = ‘threshold-entropy’

The four first options require training a shadow model, the two last options don’t.

Again, as explanations in the library are provided mainly within the code, I’d like to summarize them here:

- In threshold attacks, for a given threshold value, the function counts how many training and how many testing samples have membership probabilities larger than this threshold. The value is usually between 0.5,(random guessing between the two options member and non-member), and 1 (100% certainty of membership) Furthermore, precision and recall values are computed. Based on these values, an interpretable ROC curve can be produced representing how accurate the attacker can predict whether or not a data point was used in the training data. This idea mainly relies on [2], as stated in TensorFlow Privacy.

- For trained attacks, the attack flow involves training a shadow model as described above. A comment in the library’s code states that it is currently not possible to calculate membership privacy for all samples as some are used for training the attacker model. Here, the results display an attacker advantage based on the idea in [3].

Concerning the interpretability of the results, a library code comment states the following:

# Membership score is some measure of confidence of this attacker that

# a particular sample is a member of the training set.

#

# This is NOT necessarily probability. The nature of this score depends on

# the type of attacker. Scores from different attacker types are not directly

# comparable, but can be compared in relative terms (e.g. considering order

# imposed by this measure).

#

# For a perfect attacker,

# all training samples will have higher scores than test samples.

Now, that we know what to feed into the attack, we can run it on our model. I decided to use a simple threshold attack and a trained attack based on logistic regression for the example. I, furthermore, decided to do some slicing

attack_input = AttackInputData(

logits_train = logits_train,

logits_test = logits_test,

loss_train = loss_train,

loss_test = loss_test,

labels_train = train_labels,

labels_test = test_labels

)

slicing_spec = SlicingSpec(

entire_dataset = True,

by_class = True,

by_percentiles = False,

by_classification_correctness = True)

attack_types = [

AttackType.THRESHOLD_ATTACK,

AttackType.LOGISTIC_REGRESSION

]

attacks_result = mia.run_attacks(attack_input=attack_input,

slicing_spec=slicing_spec,

attack_types=attack_types)

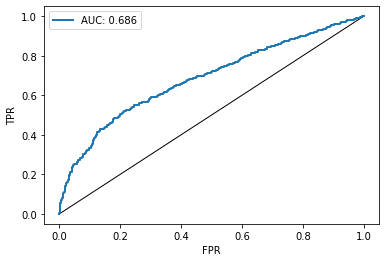

The attack_result object can provide us some thorough insight into the attack results by calling:

print(attacks_result.summary(by_slices=True))

This yields a listing of the maximal successful attacks on each slice in the form of AUC-scores and attacker advantage.

Best-performing attacks over all slices

LOGISTIC_REGRESSION (with 2889 training and 2889 test examples) achieved an AUC of 0.69 on slice CORRECTLY_CLASSIFIED=False

LOGISTIC_REGRESSION (with 2889 training and 2889 test examples) achieved an advantage of 0.31 on slice CORRECTLY_CLASSIFIED=False

Best-performing attacks over slice: "Entire dataset"

LOGISTIC_REGRESSION (with 10000 training and 10000 test examples) achieved an AUC of 0.59

LOGISTIC_REGRESSION (with 10000 training and 10000 test examples) achieved an advantage of 0.16

...

What is interesting to observe is that the highest advantage is achieved on mis-classified instances. This is a phenomenon that can be observe often in membership inference attacks, especially when overfitting the training data as much as we do with our simple model. It results from the fact that the model classifies training instances quite well, whereas it has issues on previously unseen data. Therefore, the attacker model might learn the simple connection: “if an instance is misclassified, it is likely that the model has not seen it before”, hence, the data was not used for training.

In addition to a written summary, you can also plot the ROC curve of the most successful attack

import tensorflow_privacy.privacy.membership_inference_attack.plotting as plotting

plotting.plot_roc_curve(attacks_result.get_result_with_max_auc().roc_curve)

In the following weeks, I am planning to write another blogpost about the papers [2] and [3] explaining in more detail how the results can be interpreted. For the time being, you can just take the results as they are and use them to compare between classifiers trained with different parameters and methods. I strongly encourage you to use my notebook and play around with some parameters (training epochs, batch size, model architecture etc.) in order to get a feeling how those parameters might influence membership privacy. You might also want to rebuild the entire example for another dataset, such as MNIST, in order to compare magnitudes of the attack results.

Factors Influencing the Risk of Membership Inference Attacks and Protective Measures

There has been quite some research conducted about factors that encourage membership inference attacks. For example [3] and [4] deal with the question of identifying factors that influence membership inference risks in ML models. Those factors are:

- overfitting,

- classification problem complexity,

- in-class standard deviation

- type of ML model targeted.

For those of you interested in the topic, I suggest going through the papers linked below for a deeper understanding of why these factors might have an influence.

Apart from training models that do not overfit to the training data too much, a method that helps preventing membership inference risk is called Differential Privacy. I would definitely like to introduce you to this concept in one of my future blog posts.

I hope that my post was helpful for you, if you have any further questions, remarks, or suggestions, please get in touch!

Further Reading

[1] Shokri, Reza, Marco Stronati, Congzheng Song, and Vitaly Shmatikov. “Membership inference attacks against machine learning models.” In 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), pp. 3-18. IEEE, 2017.

[2] Song, Liwei, and Prateek Mittal. “Systematic evaluation of privacy risks of machine learning models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.10595 (2020).

[3] Yeom, Samuel, Irene Giacomelli, Matt Fredrikson, and Somesh Jha. “Privacy risk in machine learning: Analyzing the connection to overfitting.” In 2018 IEEE 31st Computer Security Foundations Symposium (CSF), pp. 268-282. IEEE, 2018.

[4] Truex, Stacey, Ling Liu, Mehmet Emre Gursoy, Wenqi Wei, and Lei Yu. “Effects of differential privacy and data skewness on membership inference vulnerability.” In 2019 First IEEE International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Intelligent Systems and Applications (TPS-ISA), pp. 82-91. IEEE, 2019.

[5] Salem, Ahmed, Yang Zhang, Mathias Humbert, Pascal Berrang, Mario Fritz, and Michael Backes. “Ml-leaks: Model and data independent membership inference attacks and defenses on machine learning models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.01246 (2018).