Attacks against Machine Learning Privacy (Part 1): Model Inversion Attacks with the IBM-ART Framework

Published:

Machine learning (ML) is one the fastest evolving fields out there, and it feels like every day, there are new and very useful tools emerging. For many scenarios, creating functional and expressive ML models might be the most important reason to use such tools. However, there is a large number of tools offering functionalities that go beyond simply building new and more powerful models. Instead they offer new perspectives by focussing on different aspects of ML.

One such aspect is model privacy. The general topic of data privacy seems to receive a lot of attention also outside the tech community in the last years, especially after the introduction of legal frameworks, such as the GDPR. Yet, the topic of privacy in ML seems to be more of a niche. This bling spot is a pity and also risky since breaking the privacy of ML models can be really simple. In today’s blog post I would like to show you how. Therefore, I’ll first give a short introduction about privacy risks in ML, then I’ll present a specific attack, namely the model inversion attack, and finally I’ll show you how to implement model inversion attacks with the help of IBM’s Adversarial Robustness Toolbox.

Part 1: Privacy Issues in Machine Learning

Just to briefly provide an understanding of privacy in ML, let’s have a look at general ML workflows. This section only serves to give a very short and informal introduction in order to motivate the main topic of this blog post. For a formal and thorough introduction to ML, you may want to check out other resources.

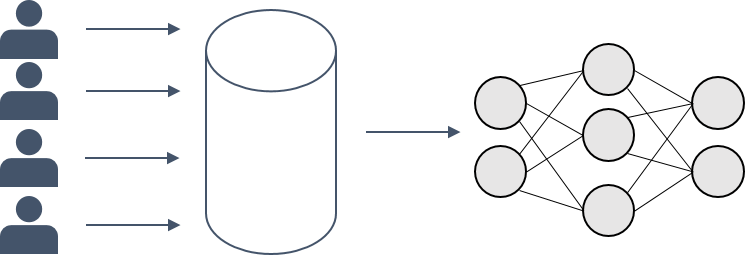

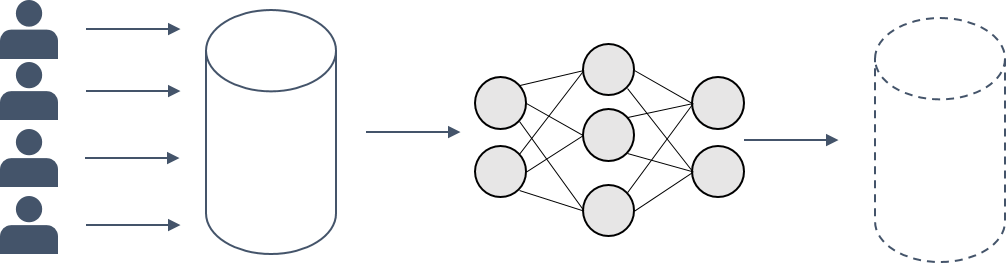

Imagine, you would like to train a classifier. Usually, you start with some (potentially sensible) training data, i.e. some data features $X$ and corresponding class labels $y$. You pick an algorithm, e.g. a neural network (NN), and then you use your training data to make the model learn to map from $X$ to $y$. This mapping should generalize well, such that your model is also able to predict the correct labels for, so far, unseen data $X’$.

What is less frequently addressed is the fact that the process of turning training data into a good model is not necessarily a one-way street. Think about it: In order to learn a mapping from specific features to corresponding labels, the model needs to “remember” in its parameters some information about the data it was trained on. Otherwise, how would it come to correct conclusions about new and unseen data?

The fact that some information about the training data is stored in the model parameters, might, however, cause privacy problems. This is because it enables someone with access to the ML model to deduct different kinds of information about the training data.

Part 2: Model Inversion Attacks

A very popular attack is the so-called model inversion attack that was first proposed by Fredrikson et al. in 2015. The attack uses a trained classifier in order to extract representations of the training data.

Fredrikson et al. use this method, among others, on a face classifier trained on black and white images of 40 different individuals’ faces. The data features $X$ in this example correspond to the individual image pixels that can take continuous values in the range of $[0,1]$. With this large number of different pixel values combinations over an image, it is inefficient to brute-force a reconstruction over all possible images in order to identify the most likely one(s). Therefore, the authors proposed a different approach. Given $m$ different faces and $n$ pixel values per image. The face recognition classifier can be expressed as a function $f: [0,1]^n \longmapsto [0,1]^m$. The output of the classifier is a vector that represents the probabilities of the image to belong to each of the $m$ classes.

The authors define a cost function $c(x)$ concerning $f$ in order to do the model inversion. Starting with a candidate solution image $x_0$, the gradients of the cost function are calculated. Then, gradient descent is applied, and $x_0$ is transformed iteratively in each epoch $i$ according to the gradients in order to minimize the cost function. After a minimum is found, the transformed $x_i$ can be returned as the solution of the model inversion.

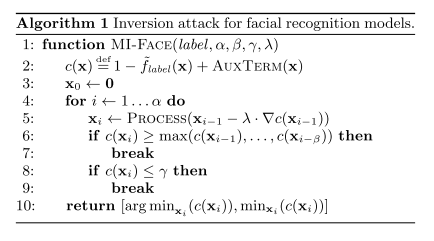

Let’s have a concrete look at the algorithm specified in the Fredrikson paper with the parameters being: $label$: label of the class we want to inverse, $\alpha$: number of iterations to calculate, $\beta$: a form of patience: if the cost does not decrease within this number of iterations, the algorithm stops, $\gamma$: minimum cost threshold, $\lambda$: learning rate for the gradient descent, and $AUXTERM$: a function that uses any available auxiliary information to inform the cost function. (In the case of simple inversion, there exists no auxiliary information, i.e. $AUXTERM=0$ for all $x$.)

As we can see, in the algorithm the cost function is defined based on $f$’s prediction on $x$. $x_0$ is initialized (e.g. here as a zero vector), then for the number of iterations, the gradient descent step is performed and the new costs are calculated. There are two stopping conditions that interrupt the algorithm: (1) if the cost has not improved for the last $\beta$ epochs, and (2) if the costs are smaller than the predefined threshold $\gamma$.

At the end of the algorithm, the minimal costs and the corresponding $x_i$ are returned. As, in the case of Fredrikson, each individual corresponds to a separate class label, the model inversion can be used in order to reconstruct concrete faces, such as the following:

Part 3: Implementing a Model Inversion Attack

Now let’s see how to put this theory into practice.

IBM Adversarial Robustness Toolbox

As stated before, nowadays, there exist several great programming libraries for machine learning and the IBM Adversarial Robustness Toolbox (IBM-ART) is definitely one of them.

Unlike what the name suggests, IBM-ART is by far not limited to functionality concerning adversarial robustness, but also contains methods for data poisoning, model extraction, and model privacy.

As most of my research is centred around model privacy, I was very keen on trying out the broad range of functionalities offered for the latter one. Next to membership inference attacks, and attribute inference attacks, the framework also offers an implementation of model inversion attacks from the Fredrikson paper.

Using ART to Implement a Model Inversion Attack

IBM-ART offers a broad range of example notebooks to illustrate different functionalities. However, there are no examples of model inversion attacks. Therefore, I thought it might be useful to share my experience on how to use IBM-ART’s model inversion in combination with tensorflow. You can download the entire notebook with my code here.

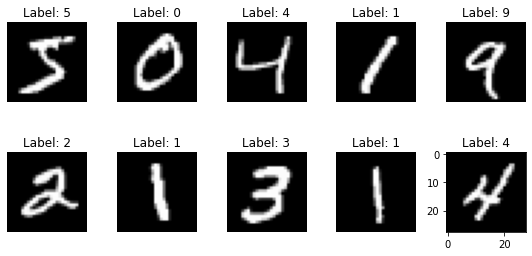

I decided to use the MNIST dataset which consists of 60.000 training and 10.000 test black and white images of the digits from 0 to 9 with the corresponding labels, such as:

Let’s get started with building our own model inversion: When you are working with tensorflow 2, the first thing to make sure is that you disable the eager execution because otherwise IBM-ART would not work. Therefore, just add the following line after your tensorflow import:

import tensorflow as tf

tf.compat.v1.disable_eager_execution()

From IBM-ART, you mainly need to import the two following things:

from art.attacks.inference import model_inversion

from art.estimators.classification import KerasClassifier

The KerasClassifier is a wrapper for your tf.keras model in order to be used by the attacks. Apart from this, the workflow is pretty similar as every other ML workflow.

First, we need to specify a model architecture. I chose for a simple ConvNet architecture, but you are, of course, not limited to that.

def make_model():

""" Define a Keras model"""

model = tf.keras.Sequential([

tf.keras.layers.Conv2D(16, 8,

strides=2,

padding='same',

activation='relu',

input_shape=(28, 28, 1)),

tf.keras.layers.MaxPool2D(2, 1),

tf.keras.layers.Conv2D(32, 4,

strides=2,

padding='valid',

activation='relu'),

tf.keras.layers.MaxPool2D(2, 1),

tf.keras.layers.Flatten(),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(32, activation='relu'),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(10, activation='softmax')

])

return model

After you’ve built the model, you can compile it with parameters of your choice:

model = make_model()

optimizer = tf.keras.optimizers.SGD(learning_rate=0.1)

loss = tf.keras.losses.SparseCategoricalCrossentropy(from_logits=True)

model.compile(optimizer=optimizer, loss=loss, metrics=['accuracy'])

Then, before training on MNIST training data and labels that I stored in the variables train_data and train_labels after preprocessing, you need to put the model into the wrapper:

classifier = KerasClassifier(model=model, clip_values=(0, 1), use_logits=False)

classifier.fit(train_data, train_labels,

batch_size=264, nb_epochs=10)

Once the model is trained, we can start attacking it.

my_attack = model_inversion.MIFace(classifier)

The model inverson attack in the IBM-ART offers you to specify arrays $x$ and $y$. $y$ contains class labels for the classes to be attacked. $x$ contains the initial input to the classifier under attack for each class label. (This corresponds to $x_0$ in our algorithm above.) When $x$ is not specified, a zero array is used as an initial input to the classifier for inversion.

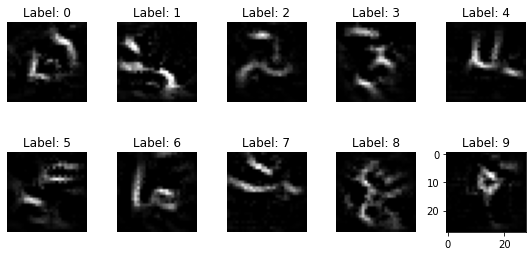

I ran the experiment with different numbers of training epochs and this is the result:

Note: The data that is returned by the model inversion attack somehow is an average representation of the data that belongs to the specific classes. In the presented setting, it does not allow for an inversion of individual training data points. In the Fredrikson example, however, every individual within the face classifier represents their own class. Therefore, the attack can be used in order to retrieve information about individuals and break their privacy.

It turns out that especially when the classifier is trained only for one epoch, many of the inversed digit representations are somehow recognizable. I hope that this example was useful for you in order to understand how simply your ML models can be attacked nowadays, and how easily you can implement privacy attacks with help of the right tools.

If you have any questions, comments, suggestions, or corrections, please feel free to get in touch.

Further Reading

[1] Fredrikson, Matt, Somesh Jha, and Thomas Ristenpart. “Model inversion attacks that exploit confidence information and basic countermeasures.” In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, pp. 1322-1333. 2015.

[2] Nicolae, Maria-Irina, Mathieu Sinn, Minh Ngoc Tran, Beat Buesser, Ambrish Rawat, Martin Wistuba, Valentina Zantedeschi et al. “Adversarial Robustness Toolbox v1. 0.0.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.01069(2018).